At Force Science, we periodically hear that perception and reaction time might apply to drivers, athletes, and pilots, but it does not apply to highly trained police officers when facing lethal threats.

The theory, as I understand it, is that police officers have undergone specialized training that allows them to intensely focus on an armed person, accurately perceive their intent, and calmly attempt to de-escalate them before the suspect shoots someone.

If the assault is initiated by the suspect, the officer will expect it, instantly recognize it, and automatically respond with such speed and accuracy as to immediately and decisively stop the threat. Under this theory, the perception, decision, and expert response will occur within 0.25 seconds—the time it can take for a suspect to quickly point and shoot at potential victims.

Many of you already recognize the absurdity of this “superhuman cop” myth.1 We addressed this topic and the relevant Force Science peer-reviewed research in You Don’t Have to Shoot First; But You Better Do Something! There, we observed if the officer immediately recognized the gun as it was being aimed in their direction, and if we assign an average response time of .83 seconds observed in the lab, the suspect will still be able to pull the trigger 3 or 4 times before the officer would be expected to fire once. “That’s assuming the incoming rounds didn’t extend the officer’s response time…or prevent it altogether.”

I’ll highlight another observation from that article that challenges the “highly trained officers can outdraw suspects” argument:

In the real world, officers do not have the luxury of standing perfectly still and intently focusing on possible weapons. They are scanning for available cover, improving their position, watching for crossfire, considering backdrops, attempting de-escalation, communicating with responding units, and coordinating with back officers.

This divided attention can significantly increase the time it takes for an officer to accurately perceive and consciously verify that a suspect has pulled a gun. But multitasking isn’t the only factor that affects perception and threat recognition.

In the real world, an officer’s physical capacity to see can affect perception, identification, and response time. As can environmental conditions like distance, light, shadows, wind, rain, and other physical obstructions.

We know that divided attention, physical limitations, and the environment can slow perception and response time; the question is, by how much? The answer is, we don’t know.

What we do know is that real-world shootings and reality-based training have involved response times measuring between 2-3 seconds, while suspects were able to shoot in 0.25 sec. or less.

Outside Research

While Force Science has conducted and published the results of its studies on action/response times, we use more than our own peer-reviewed research to inform decision/action/response analysis in force encounters.

Extensive outside research from decision-making experts, traffic safety experts, and sports performance researchers begins to detail what we can expect from humans involved in decision-making and performance. The following is provided for those needing to understand the reality of human performance, and those hoping to debunk the myth of the superhuman cop.

Making Decisions Takes Time

Experts almost universally categorize the process for making judgments into two categories, those that are conscious, slow, and deliberate (e.g., analytical, System 2, rational) and those that are unconscious, rapid, and automatic (e.g., intuitive, System 1, heuristic)2

Whether a person is relying on the “top-down” analytical processes or the faster intuitive or heuristic processes—decision-making takes time.

Dr. Marc Green is a human factors expert with over 45 years of research experience. Dr. Green has authored over 100 publications in the areas of vision, visual search, attention, perception, reaction time, and human cognition.

Although, Dr. Green is known for his extensive research and writing in the field of traffic safety, he applies his research to police performance, including police deadly force decision-making.3 For those that imagine that traffic safety studies are irrelevant to police, the experts disagree. Dr. Green has written specifically on police applications and is an expert in police use of force cases.

In his writings, Dr. Green describes the four substages of mental processing as:

- The time it takes to detect the sensory input (“sensation”).

- The time needed to recognize the meaning of the sensation (“perception/recognition”).

- The time needed to interpret the scene, extract its meaning, and consider its future effects (“situational awareness”).

- The time necessary to decide which, if any, response to make and to mentally program the movement (“response selection and programming”).4

Once a decision to respond is made, people still need to physically perform the required movements. This movement also takes time and can be influenced (faster or slower) by the emotional arousal of the person.

If the response involves an object (e.g., holster, firearm, or TASER), the response will require additional time to manipulate the object’s features (e.g., an officer drawing a gun must defeat the holster’s retention features, manipulate a safety, and then press the trigger to fire the gun.) With firearms, it also takes time to reset or release the trigger so that it can be manipulated (“pressed”) again. This “cycling” of the trigger also takes time.

Together, mental processing time, movement time, and device manipulation time make up the “response time” (“reaction time” and “response time” are sometimes used for the same concepts).5

Response time components can be studied independently, but they are not necessarily performed consecutively. For example, to save time, some officers will move to their holster and draw their gun while still assessing the threat. Others will release the safety and move their finger to the trigger while simultaneously presenting their pistol toward an imminent threat.

Analyzing Decision-Making in Force Encounters

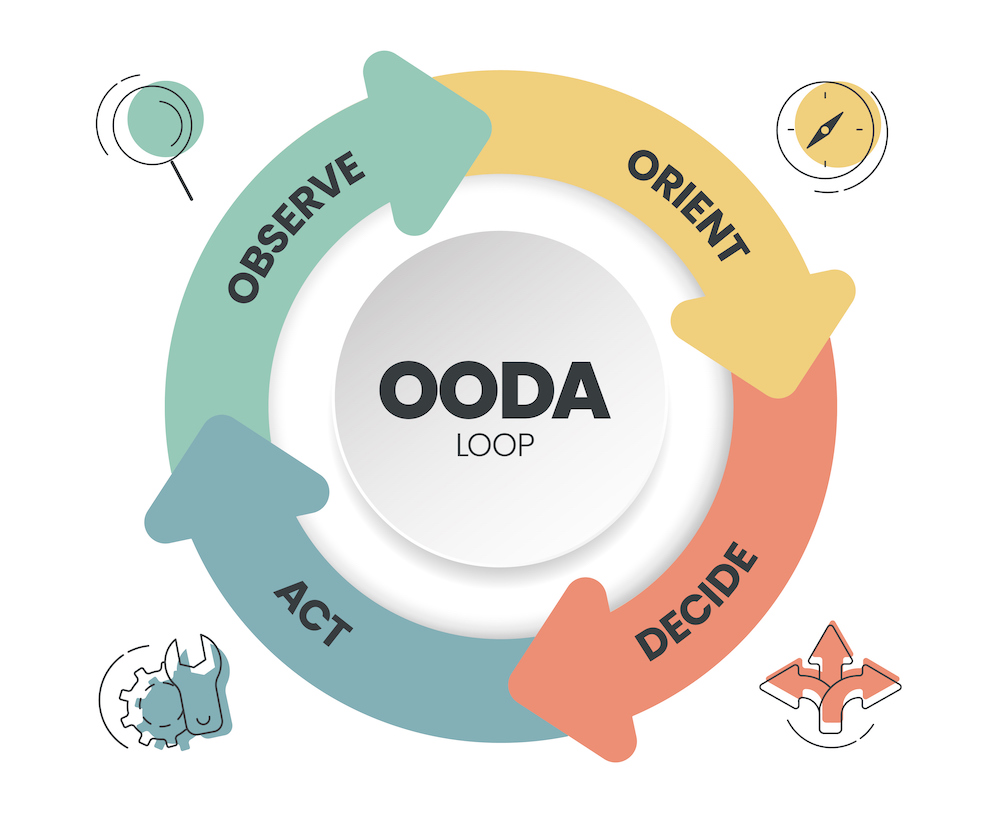

The concepts of reaction time and response time are well understood and considered in law enforcement by trainers, investigators, and those who evaluate use of force encounters. The concept of the “OODA Loop” loosely corresponds with the response time components recognized by Dr. Green.

OODA is an acronym commonly understood and utilized in law enforcement to evaluate response time. OODA stands for Observe (perceive), Orient (recognize/assign meaning), Decide (response selection/programming), and Act (physical movement/device manipulation).

While individual research might identify average performance times within that study’s population, there is no single, universal reaction time or response time. As Dr. Green details, reaction time can be affected by whether the stimulus (“threat”) was expected, unexpected, or a surprise. According to Dr. Green’s research, braking time can double, depending on whether the stop signal is expected or unexpected. The same issues should be considered when evaluating police performance.

Factors Affecting Reaction Times

Reaction time can be affected by perceived urgency, the mental effort required for problem-solving (“cognitive load”), the ease and naturalness of the response (“stimulus-response compatibility”), the clarity of the stimulus (i.e., how obvious was the weapon or predictable was the threat), visibility, and complexity of the response.

Uncertain and vague threats can make decision-making during force encounters extremely difficult. Adding to this difficulty, the number of response options can further impact decision-making and overall response times. Consider the following categories of stimulus/response conditions and their expected impact on response times.

Simple Reaction Time

All things being equal, if there is a single possible stimulus and a single response (“simple reaction time”), reaction time is expected to be the fastest. For example, Olympic sprinter, Usain Bolt, took eighteen hundredths (.18) of a second to react to the sound of the starter’s gun when he set the world one-hundred-meter record. However, simple reaction times are rarely the case in force encounters.

Complex Choice Reaction Time

If there are multiple possible signals, each requiring a different response (“complex choice”), then reaction time would be expected to increase as people interpret the varied conduct and choose the related response (i.e., the suspect can engage in a variety of actions, some threatening, some innocuous). Reaction times are expected to slow as more choices are considered. This is frequently the case in force encounters.

Recognition Reaction Time

If there are multiple possible signals but only one response (“recognition reaction time”), reaction times would be expected to be longer than simple reaction times (e.g., a sniper may be singularly focused on assessing a lethal threat. While the negotiator communicates, the sniper may perceive varied conduct. Even so, the sniper has only one choice (go/no go) when confronted with a lethal threat stimulus. Of course, that lethal threat stimulus can be clear or ambiguous based on the context, with ambiguity expected to add to the interpretation of the threat and overall response time.

Speeding Up Decision-Making

Dr. Gary Klein, the creator of the Recognition Primed Decision (RPD) model, coauthor with Nobel Prize winner Dr. Daniel Kahneman and developer of a decision training program for California POST, informs us that once officers perceive a situation, they can more rapidly assess because of their ability to recognize patterns in the incident (“heuristics”).

Dr. Marc Green described a similar process in driving, in that we can rapidly, almost automatically make decisions because of previous experience. For example, the automatic process of braking or accelerating when unexpectedly perceiving a green light changing to yellow at the intersection.

Even in an incident involving expected events, the perception and detection process, although rapid, still takes time and is based on experienced and identified patterns (“schemas”). In policing, the identified patterns come from the officer’s training and from past experiences involving similar “contextual elements” perceived in the current incident.

Dr. Klein and Dr. Green’s observations are not controversial. Academics frequently called to testify against police officers have been forced to admit that officers are unlikely to make slow, analytical decisions in situations involving physical force. During potentially lethal encounters and other high-pressure situations, it is reasonable to expect that officers may instead rely on intuition and experience (heuristics or “rule of thumb”).6

What is also reasonable to expect is that police, like all humans, are constrained and influenced by the psychological, physiological, and environmental limits affecting perception, decision-making, and performance. Even the most ardent anti-police experts have been forced to admit this. And for those imagining that police receive training that eliminates the action/response gap, none have come forward to explain exactly what that training might be or where the officers have been receiving it.

- See Calibre Press, Cops Are Not Super-Humans. Understanding the Experts Who Explain That at https://calibrepress.com/2023/05/cops-are-not-super-humans-understanding-the-experts-who-explain-that/ [↩]

- Dual-Processing Accounts of Reasoning, Judgment, and Social Cognition [↩]

- See “Is It A Gun? Or Is It A Wallet?’” Perceptual Factors In Police Shootings of Unarmed Suspects,” Police Marksman, July/August, pp 52-54, 2005; see also “Proper Eyewitness Identification

Procedures,” Law and Order, pp. 195-198, October 2003. [↩] - See “‘How Long Does It Take To Stop?’ Methodological Analysis of Driver Perception-Brake Times,” Transportation Human Factors, 2, 2000. [↩]

- See Motor Learning and Performance, 6th Edition, Schmidt and Lee, 2020; Perception, Cognition and Decision Making, Vickers, 2007. [↩]

- See Hine, K. A., Porter, L. E., Westera, N. J., Alpert, G. P., & Allen, A. (2018). Exploring Police Use of Force Decision-Making Processes and Impairments Using a Naturalistic Decision-Making Approach. Criminal Justice and Behavior. doi: 10.1177/0093854818789726 citing Alpert, G., & Rojek, J. (2011). [↩]

So true and so non-intuitive! The idea of a firearms naive offender accurately firing 3-4 rounds at you in 1 second seems impossible but it’s true. This is why Realistic De-escalation training is so crucial for survival..One important point that Klein and Kahneman differ on is the immediate appreciation of absent important environmental cues. Klein’ a most famous analogy is of the fire commander who evacuated a burning building because it was too quiet. The fire was in the basement below him and the floor immediately collapsed upon his team exiting the structure. Kahneman would say WYSIATI: what you see is all there is.

His “always on” system 1 would not appreciate the important absent cue. However, they remain buddies despite this and we can learn much from both of them. I highly recommend Klein’s Sources of Power and Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. Treatises..

Stay safe out there.

Excellent and well-written article on reaction time.

I’m running a 3-day camp for martial arts instructors in September & one of our topics is “reducing reaction time to street attacks.” I’d like to use this article as prerequisite/recommended reading before my instructional sequence. If possible I’d also like to make this article available to other members on my mailing list. Who would I contact for such permission?

I’ll contact you. Thanks!

For the day to day patrol officer or detective the common factor is complacency! Depending totally on the contacts reaction to the contact!

Information is so important to the initiating stop via Lucy plate info or veg description before leaving the safety of their own vehicle. Unwarranted movements of people in the vehicle are tale tale signs that something is amiss. If the vehicle being stopped pulls off the road to an unlighted area or an alley again that’s an indicator!

Now as for special teams they too can become complacent because complacency in training , leadership and or attitude! We have advantage; yes and no! Shit happens!!!

Great article I am involved in an upcoming court case revolving around an officers use of force this may be a big help in explaining aspects of decision making to the jury.