Editor’s Note: Dr. Geoff Desmoulin and his team at GTD Scientific continue to provide the highest caliber injury biomechanics and reconstruction expertise for force investigators and courts. Dr. Desmoulin recently presented at the Romanian Forensic Scientists Association Conference and has been selected as a keynote speaker for the 2023 Daigle Use of Force Summit. This article was originally published in the July/Augugust 2023 issue of Blue Line Magazine and is republished here with their permission.

Police officers face many unexpected challenges and risks each day on the streets, and it’s crucial that they have access to reliable equipment that can help them respond effectively to dynamic and unpredictable situations. However, the market is flooded with new and innovative products that claim to be tactical and efficient for law enforcement officers.

While many departments do not object to the use of aftermarket products, the case of a recent officer-involved shooting1 highlights the potential risks associated with such untested equipment. In this incident, an officer’s holster failed during a struggle with a suspect, which forced the officers to defend themselves with lethal force. Upon investigation, it was found that the failure was not due to the holster itself, but rather an aftermarket product that had been added by the officer. This paper seeks to examine the incident and explore the importance of carefully choosing equipment to ensure the safety and integrity of both officers and the public they serve.

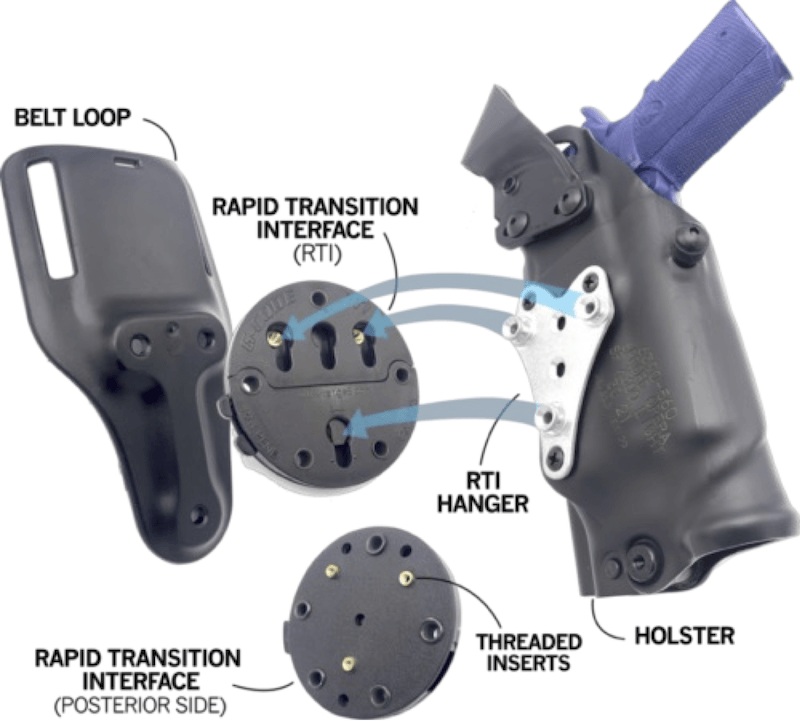

The product involved in this incident was a model of a Rapid Transition Interface (RTI) Wheel (since discontinued), which was ripped from an officer’s belt loop during a dynamic struggle. The purpose of the RTI Wheel is to allow the user to quickly reposition the holster to another location and platform without removing the entire belt loop attachment and for this reason, this optional accessory sits between the holster and the belt loop (as shown in Figure 1). The failure which occurred in this incident was due to the malleability of the material located on the posterior side of the RTI, which allowed its threaded inserts to be pulled out from its back plate.

Testing performed by GTD Scientific in the context of an investigation into this incident revealed that the product’s design made it possible for a determined individual to separate the holster from an Officer’s belt with an effort of approximately 75 percent of an adult male’s maximal pulling effort in less-than-ideal conditions. Although the magnitude of force involved in this failure was significant, law enforcement officers are expected to be exposed to determined and noncompliant individuals. Therefore, the possibility of this failure should not have taken the officers involved by surprise. Had proper testing been performed to identify this shortcoming, the design could have been improved and therefore the death involved in this incident could potentially have been avoided.

As can be imagined, statements created by advertising teams are a poor substitute for independent testing.

This incident highlights a proposed framework for equipment evaluation that dates back to 2004. Rappert, 20042 proposed that all new less-lethal equipment assessments be guided by four specific principals. The suggested principles are generalizable to all new equipment and when doing so can be reduced to three and are highly applicable here. The adopted three principles are found below.

Principle 1: Police should not be left alone to regulate themselves regarding the evaluation of the equipment they use.

While government forces undergo legal scrutiny, typically much of this activity is restricted to a limited number of non-technical individuals internal to the agencies. This is demonstrated by the wide range of discretion left to individual officers’ choice of equipment. For example, some departments allow officers to purchase their own equipment, while others assign equipment to their officers. The latter may have prevented the incident described above if implemented appropriately to include field tests and biomechanical assessments, but these policies also have drawbacks, such as limiting officer choice and potential innovation. These drawbacks could be overcome by testing various popular equipment choices.

Principle 2: Manufacturers’ statement of the efficacy of equipment should not be taken on faith.

Marketing claims should be examined by governmental and non-governmental agencies, not demonstrated by manufacturers. As can be imagined, statements created by advertising teams are a poor substitute for independent testing. One such claim stated that mace reduced assaults on police officers by as much as 50 percent, but time and experience proved this “statistic” was grossly overestimated (Faulkner & Danaher, 1997).3

Principle 3: Equipment functional uncertainties should be minimized.

By far the most difficult principle to achieve is the goal of understanding new, untested technology and the complex operational environment in which it will be used. It must remain a goal nonetheless as the example above demonstrates. A few steps to achieve this principle are suggested:

- Follow scientific methodology;

- Avoid obvious risk by exploring material limits of typical equipment use;

- Avoid less obvious risk by exploring non-typical use scenarios;

- Relate all data back to human capabilities;

- Learn from the knowledge produced.

The recent incident involving a holster failure during an officer-involved shooting serves as a stark reminder of the potential risks associated with aftermarket products. Agencies should consider in-house biomechanical testing in-line with the above stated principles to ensure that equipment is both safe and effective. Basic biomechanical testing can provide valuable information in a relatively inexpensive and short amount of time. The results of such testing can potentially save the department thousands in litigation costs, avoidable catastrophic injury and uninformed purchasing of poor performing equipment should it fail in the field.

Geoffrey T. Desmoulin, PhD., RKin., PLEng., is the Principal of GTD Scientific Inc. in North Vancouver, whose core competency is Biomechanical Engineering. He can be reached at gtdesmoulin@gtdscientific.com.

- “Officer Involved Shooting, Suspect broke holster from officer’s duty belt.” San Diego, CA, 2020. [↩]

- Rappert, Brian. “A framework for the assessment of non-lethal weapons.” Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 20:1, 35-54. 2004. [↩]

- Faulkner S, Danaher L. (1997) Controlling Subjects: Realistic Training vs. Magic Bullets. Accessed at www.fbi.gov/publications/leb/1997/feb974.htm. [↩]

I bought a second chance vest and speed loaders long before anyone was issued them. And after an incident i went from a suicide strap holster to a thumb break (Safariland by the way)

Scary. Hope you werre not injured in the “incident”.

They issued you a second chance vest? I had to buy mine in 1973. Three easy payments of $85. We test all we use because Officers always see good gee-whiz stuff that looks good on paper. And it will work till some AO tries to test it for you.

Sounds awesome David. I’d be interested to know your definition of “tested” as I find it a loaded word and up for interpretation depending on your industry.

A few years ago we had a training class come from the Academy with about six rookies that decided to add “hood” locks to their holsters…without checking to see if they were authorized. (They were prohibited). The reason they did this, during defensive tactics training, the instructors kept stealing their training guns. Rather than learn to defend their weapon better, they resorted to that gadget.

When they showed up on my range, all six had trouble making their call times because they couldn’t draw fast enough. it turns out due to the amount of people at the Academy that year, they had finished their range qualifications before they finish their DT. So they never got to pressure test the equipment.

I was particularly upset that the DT instructors didn’t find the unauthorized modifications on their holsters when they started retaining their guns. I made them remove them right there and then. Sure enough, they were able to draw just fine.

Awesome!

Great article and very informative. There are some departments, that are having some very serious budget problems and officers are purchasing their own equipment, such as the M4 with optics. I strongly recommend before any equipment is purchased an evaluation including a demonstration of the equipment is done. From what I understand there are training videos on line, showing how to disarm officers. I am a 35 year retired police officer, firearms instructor and recipient of the medal of valor. Stay safe folks!

Thank you Jerry for the positive feedback and service.

As a former department trainer, I fought many battles on this subject.

Thank you sir!

I always caution about buying goods that may turn out to be counterfeit on online shopping sites such as ebay or amazon

I would agree. Specifically when taking the “Stop the Bleed Course” via Spartan Training they had “tested” many TQ’s via reputable vendors and those acquired through Amazon. Not surprisingly some of the Amazon product while marketed as G7 TQ’s failed miserably in the turn tightness test.

Ok, so most of the time I agree with everything Force Science, but I can’t bring myself to fully agree with this one. First the term “after-market” covers a wide variety of parts and accessories that encompass most aspects of policing. First patrol cars; do any vehicle manufactures make prisoner cages, light bars, push bumpers, or computer mounts? Next let’s look at firearms, not all rifle manufacturers make magazines, does this mean we shouldn’t buy rifles unless the manufacturer also makes magazines? Finally let’s look at the incident used as an example. There have been several officers locally that shot suspects who were either trying to take their firearms, or trying to take another officer’s firearm. None of the officers I am familiar with were prosecuted even though the suspect was unsuccessful in obtaining the firearm. The use of force in each case was deemed justified.

Let’s not forget that everything with parts will break with enough time or force regardless of the name on the emblem.

As a parting note, I challenge anyone reading this comment to do a web search for their favorite name brand holster with the word failure after it and see what you turn up. Per this article those are not after-market, but they also fail.

Stay safe out there.

I remember in the 1980s when similar holsters were in use to allow the holster to be positioned in seats, on foot, and on motorcycles. This holster was approved by the the department and they failed at a similar interface point causing the officer to lose both the holster and firearm. I also remember the same metropolitan department issuing ammunition rated to penetrate the issued body armor. Many officers switched to personally owned armor rated to stop the duty ammunition. This was in violation of department rules. The ammunition was eventually changed based upon multiple complaints from officers. Further, this same agency issued another holster that had fatal defect. When the exposed butt of the firearm was struck the firearm disengaged the holster and fell out. Fortunately this holster was replaced quickly once the defect was discovered. This issue continues today as a major problem for some agencies as reflected by the article.

This is an interesting article. I also purchased this holster mount and immediately observed the ill effect of it being ripped off of my body.

Thank you for the honesty, Anthony!

This is a great article! Thank You

You are most welcome Aaron!

Great information on the risks of using equipment not tested by an agency.

Even non “aftermarket” gear can be a problem. At my old job they had an incident where a Safariland QLS mounted on a Safariland holster separated during a gun grab from the belt shank, leaving the officer fighting over the holstered duty pistol.

There’s also the issue of an almost complete lack of preventative maintenance in most programs.

Example; I was recently running several officers through the state qual course when one of them had his Safariland ALS holster fail, because one of the bolts that holds the retention mechanism together just fell out. These had no been installed with Locktight, and the officer had not been keeping an eye on his gear.