This article was originally published in the summer 2022 issue of The Tactical Edge, the professional journal of the National Tactical Officers Association, and is reprinted with permission.

For membership information, visit https://www.ntoa.org/membership/

Law enforcement requires many skills — motor, perceptual, cognitive, decision-making — which improve and are retained with training, and deteriorate without it. When refresher training is not available or practical, or is prohibited due to limited time or resources, it is imperative to develop methods that maximize long-lasting improvements. But many trainers continue to use methods that are less effective than easy-to-use, cost-efficient alternatives. This article highlights research findings that could improve how police training programs prepare trainees for active duty. It will focus on methods of training that produce desirable difficulties, resulting in skills that are longer-lasting.

Training fails to adopt proven methods due to two illusions about learning. Some methods are excellent for promoting immediate improvements during the training sessions. However, these improvements are lost quickly and often fail to transfer beyond the initial training environment. Here, the illusion occurs because rapid performance improvements overestimate what is retained versus what merely is transferred. A second type of illusion occurs when training is difficult and performance improvements are gradual. Here, the slower improvement rate underestimates actual learning — the permanence of skills is far greater than expected.

The reason for these illusions is that trainees (and trainers, too) mistakenly equate immediate performance improvements with successful learning, when in fact, the opposite is often true.1, 2 Cramming for an exam is a good example, where a student memorizes text just before an exam. Sometimes the strategy is successful, especially if the exam occurs immediately after cramming. But cramming often results in rapid memory loss.

In contrast, reviewing the same material for an equivalent amount of study, but spaced out over longer periods of time, results in more permanent remembering. Cramming requires less effort and often the student is not concerned whether the information or skills are remembered after the exam. That is not true in most workplaces, in which the training goals are to develop knowledge and skills that are long-lasting.

Creating Desirable Difficulties in Training

Over the past 40-plus years, researchers have made discoveries that have shaken some core beliefs about how to conduct effective training. Modern views of training suggest that certain difficulties encountered during training have desirable consequences on learning.3,4 Below are five research issues that highlight the importance of desirable difficulties and have important implications for the delivery of effective and efficient police skills training.

1. The Spacing Effect

Studying for an exam by cramming represents an example of “massing” — the scheduling of training into concentrated units. Massing is often contrasted with “spacing,” where training occurs in small units, separated by periods of time when the learner is not training. The consistent finding is that spacing is much better than massing for the retention of both perceptual-motor skills and factual knowledge.5,6

For example, one study7 found that 80 hours of training postal workers was much more effective if spread over 40 or 60 days, when compared to training that was compressed into 20 days. Another study8 compared four sessions of microsurgery training completed all in one day to a spacing condition in which the four sessions were spread over four weeks. Tests of retention one month later, as well as a transfer test (surgery on a live animal), resulted in better performance for the spaced group. The spacing effect is not limited to learning perceptual-motor skills however, having been found in several educational contexts, such as learning mathematical skills.9 Overall, however, spacing effects are strongest when combined with testing, feedback, and interleaving, presented in the next sections.

2. The Testing Effect

What is the most frequently streamed Beatles’ song? “Hey Jude”? Nope. “Yesterday”? Wrong. “Get Back”? Not even close. The answer? “Here Comes the Sun.” Like most trivia, facts are easily forgotten if just read or told to you. But had you actually tried to answer this question before reading the answer then it will remain with you much longer in the future.

It is generally true that people dislike taking tests. Stress levels are elevated, particularly when the outcome has consequences. So, it is not surprising that tests, as learning tools, generally have not been used often in training, despite evidence for their benefit known for more than a century.10 Common study methods, such as reading the material, using a highlighting pen, and taking notes are moderately effective. However, they fail when compared to the effects of testing on longer term retention of information.

One study11 provides a good example. Two groups of participants each read a short story. A few minutes later one group re-read it, while the other group tried to remember the details in a test. Phase two of the study involved memory tests conducted five minutes, two days, or one week later. Like the previous discussion about cramming, reading the story twice was helpful if the test was given immediately (five-minute delay). However, those who immediately took the test fared bared than those who re-read the story in the two-day and one-week delayed tests. In other words, the test benefited longer-lasting retention of the story much more than a re-read. A second experiment by the same authors found that memory was further enhanced if multiple tests were attempted, compared to repeated reading.

The testing effect has been demonstrated often, such as using classroom settings,12 in training of health professionals,13 and perhaps of relevance to policing skills, in enhancing the memory of map details.14 Tests can also benefit memory even when given before any information is studied.15 Further, repeated tests are more effective if spaced rather than massed, consistent with the discussion in the previous section.

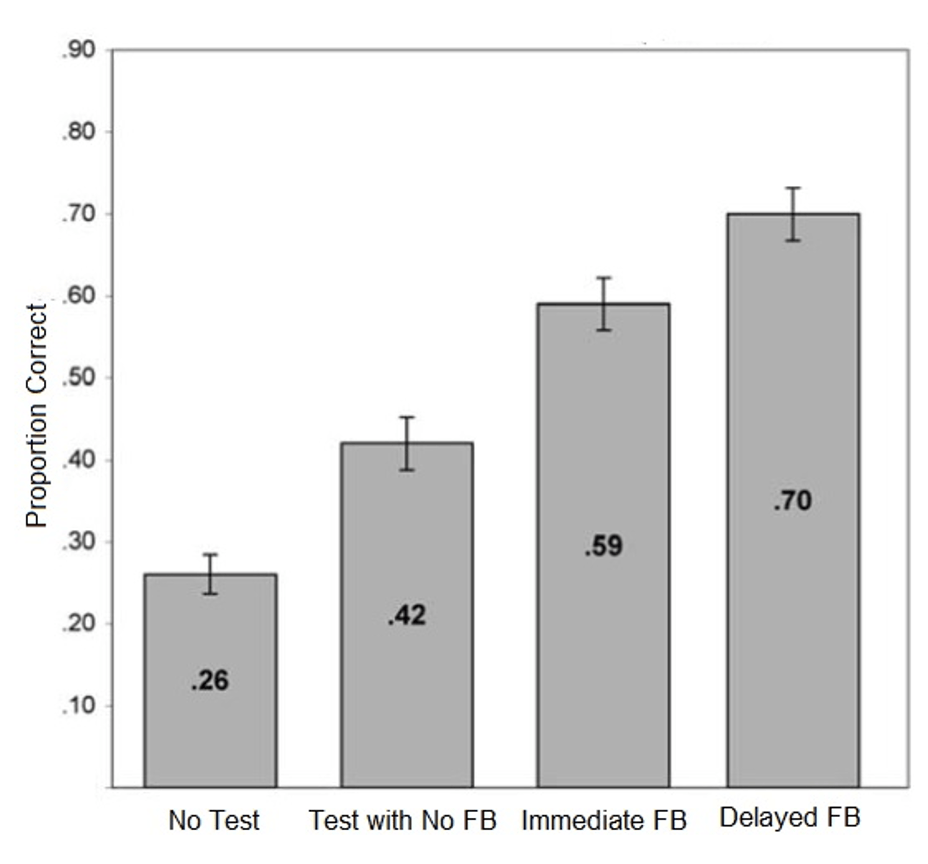

3. Delaying Feedback

The value of testing as a learning tool has been established in hundreds of research studies.16 Giving feedback (right or wrong) about the test and providing corrective information (when wrong) would seem like an obvious additional benefit. But that is true only to an extent. For example, in one study,17 participants were given material to study, followed by no test; a test without feedback; or a test that was followed with feedback provided either immediately after answering the question or one day later. A final test was given one week later. The results of this final test are illustrated in Figure 1.

Three interesting results are of note in Figure 1. One was that performing the initial test in the absence of corrective feedback produced better final test performance (0.42) than not doing the test at all (0.26), even when substantial errors were made in that initial test. Second, perhaps not surprisingly, providing feedback after the initial test (two right bars in Figure 1, average = 0.65) resulted in better final test performance than when no feedback was given (0.42). However, the third result was most interesting: giving test feedback one day later resulted in better final test performance (0.70) than giving immediate test feedback (0.59). This last finding seems counterintuitive to the idea that feedback should be provided as soon as possible after the error for it to maximally fulfill a corrective role.

Regarding the first result, note that testing in the absence of feedback underscores a very important point that it is the act itself of attempting to retrieve information from memory that serves to making information longer lasting. With regards to the role of delayed feedback, note that the effects hold true regardless of whether the feedback confirmed that the initial answer had been correct, or when the feedback provided corrective information for an initially incorrect response. In both instances the delayed feedback acts like a spacing effect. Here, the initial retrieval attempt and the feedback being spaced apart in time have a stronger impact on memory than massing the retrieval attempt and the feedback.

The delayed feedback effect also occurs in perceptual-motor skill learning. In one study18 , participants learned a simulated batting task in which the only information about performance success was provided by feedback from a computer. For one group feedback was provided instantaneously upon completing the bat swing. In the other condition the feedback was delayed by a few seconds. The task was practiced over two training sessions then tested after retention delays of 10 minutes, two days, and four months. The results showed that delayed feedback was beneficial throughout all the retention periods. Further, the beneficial effect of feedback delay was enhanced if the learner was encouraged to guess the feedback before it was provided.19

These delayed feedback results represent only a subset of findings in the perceptual-motor skills literature that are counterintuitive to many training practices. For example, providing feedback, 1) infrequently (compared to feedback as often as possible), 2) as summaries or averages (compared to feedback about individual performances), and 3) when determined by the learner (compared to feedback as determined by the instructor), have all been found to benefit learning.20 In each instance, feedback that made training more difficult resulted in a desirable effect on learning.21 This relationship between difficulty and learning has never been clearer or more frequently studied than the effect of interleaving, presented in the next section.

4. Interleaving

My children, when first learning to print, brought home a workbook with sheets that resembled the illustration in Figure 2. How would you ask a child to complete the sheet? Most parents and teachers would instruct the child to complete one row at a time. This style of repetitive or “blocked” practice is typical of most instructional/training routines. For example, over 90 percent of the examples in six popular seventh grade mathematics textbooks used in the U.S. are presented in a blocked order (e.g., repeated questions involving multiplying fractions).22 Research findings and popular opinion agree that blocked practice usually results in rapid improvements on the performance of a task (compared to mixing up practice). But is it the best way to learn — to make the improvements that last?

That question was asked of 162 first-grade children, instructing them to write the cursive letters “h” “a” and “y” 24 times either in a repetitive order (eight repetitions of one letter before a next letter was written) or in an interleaved order (also eight instances of each but in an order where no letter was practiced more than twice in succession).23 Tests of retention (performing each letter separately) and transfer (writing the cursive word “hay”) were performed better following interleaved practice. These findings replicated hundreds of research studies showing a retention/transfer advantage for perceptual-motor skill learning following interleaved practice.24

Although interleaving has been consistently shown to benefit learning, there is a reluctance by many to use it. This is likely because many of these studies found an advantage for repetitive (blocked) ordering during the training period itself. This advantage, as alluded to by the preference of using a repetitive type of practice style for the worksheet illustrated in Figure 2, is often misattributed to a learning “illusion” discussed earlier. One study,25 for example, found that participants in a repetitive practice schedule severely overestimated their actual performance in retention. Conversely, members of an interleaved group severely underestimated actual retention performance. Blocked practice gives an illusion that the learning will stick; interleaving does not — both of which are opposite to the actual result.

This illusion is true for learning perceptual skills as well as motor skills. Most painters demonstrate a particular “style” that is uniquely their own, and learning to recognize an artist’s style occurs by extracting commonalities from different paintings. How does one best learn a painter’s style? That was the question addressed in a study26 that compared blocked and interleaved presentations. Each participant in the study was presented with six samples of an artist’s work — some artists’ paintings were presented consecutively, without any other artist’s works intervening, while some artists’ paintings were interleaved with others’ paintings (no two paintings from the same artist ever presented consecutively). The results were dramatic: interleaved presentations resulted in test performance that far exceeded blocked presentations. Moreover, interleaving also resulted in better artist identification when a new, never-before seen painting was shown. Despite these two overwhelming findings, a large majority of the participants still believed that blocking the order of presentations had been more effective than interleaving. The mistaken intuition about perceived effectiveness of blocking overshadowed the actual effectiveness of interleaving.27

5. Training Under Pressure

An issue of direct relevance to the learning of policing skills is training under pressure. By their very nature, some performance situations induce heightened levels of pressure, such as piano rehearsals, the final golf holes of a club championship, university entrance exams, and specifically for policing, in dangerous confrontations. An important idea regarding training concerns how the learner has prepared for situations of elevated pressure. For example, the piano student undergoes considerable physiological changes when put under pressure — breathing and heart rate levels go up, movements are quickened, and attention is narrowed. If the learner has never experienced this situation previously then it is not surprising that performance often deteriorates under pressure. Fortunately, research suggests that some of these negative effects can be severely reduced if training conditions have been adapted to prepare the learner for performance under pressure.

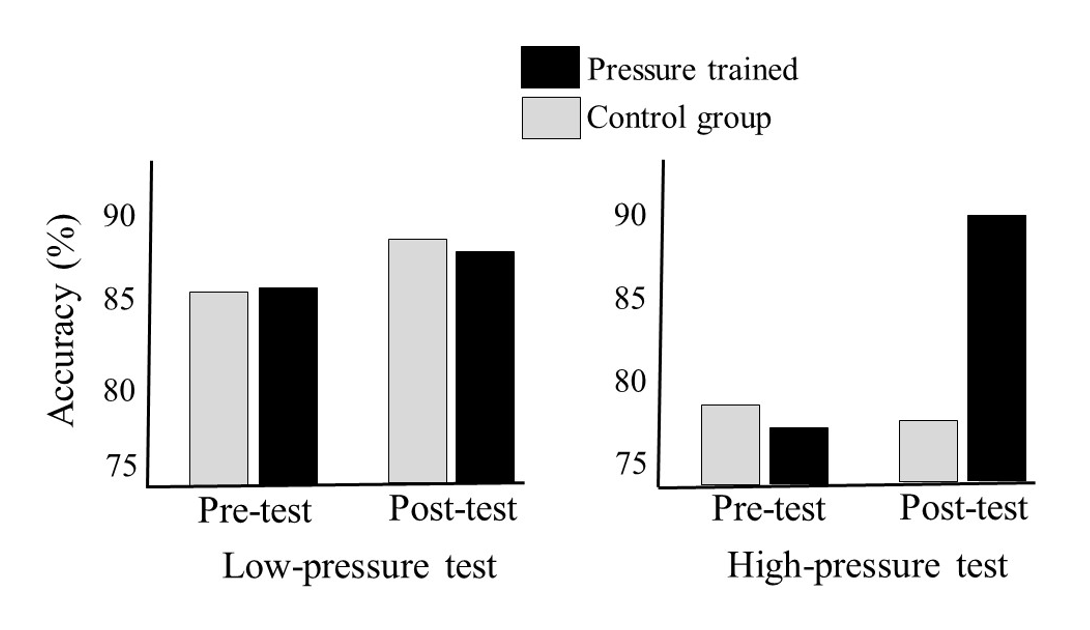

Studies have been conducted in which pressure situations were introduced into the training of previously learned or unlearned skills, such as dart throwing, golf putting, and handgun shooting.28 Various methods of inducing pressure have been used, such as performing in front of an audience, providing incentives, or in the case of some police studies, having the “target” occasionally shoot soap cartridges back at the officer.29 This research has found that training under pressure had a beneficial influence when later examined under high-pressure test situations, compared to a comparable amount of training without pressure.30 A study of SWAT trainees in China provides a good example. In the study,31 SWAT trainees were divided into two groups and underwent three, one-hour daily sessions of shooting in which a person in safety gear either stood near the target (pressure-trained group) or without anyone near the target (control group). The rationale of this pressure manipulation was to simulate the effect of shooting in a hostage situation, which might be a real-life scenario for a SWAT team member.

Shooting accuracy was assessed both the days before and after training, under both no pressure and pressure situations (i.e., with or without a person near the target), and presented in Figure 3. The left side of the figure illustrates the results of the low-pressure test — both groups improved their overall shooting accuracy as the result of practice, but not one group more than the other. The high-pressure test, on the right side of the figure, clearly illustrates the effect of training under pressure. For the high-pressure group, post-test performance was much better than on the pre-test. However, for the control group, performance on the high-pressure test was as poor in the post-test as it had been in the pre-test. These findings, like results in other studies32,33 involving law-enforcement officers, clearly support the efficacy of training under the types of pressure conditions that might be encountered following a training period.

What Makes Difficulty “Desirable”?

One way to think about what makes a training difficulty “desirable” is to consider what makes the skill difficult in the first place. For cursive writing, the skill is not to produce a string of “a’s” in a row, but rather to write words. Events that require performing differing skills in succession is true of many sports (e.g., dribbling a soccer ball past an unpredictable defender), daily activities (e.g., driving a car on a busy freeway), and in law enforcement. What is “desirable” means training the skills in ways that will later be performed — not by making them easier in ways that will not be performed later. Interleaving is desirable, albeit difficult, because skills are interleaved when they must later be performed.

The same is true of the four other areas that were discussed. Recalling information from memory is not the same as reading or marking a passage with a highlighting pen. It involves the active search and retrieval of information, which at times can be imperfect and prone to errors. However, the process of searching and attempting to retrieve information improves the process of doing it again later. In this case, the difficulty of the skill (retrieving information from memory) has been made more efficient and effective by the difficulty of the training (testing).

Delaying the process of retrieving a fact or performing an action after a period of time (i.e., spacing) has a similar effect as testing. Jacoby34 offered this excellent example. What is the sum of (37 + 15 + 12)? You could likely produce the answer in a relatively short amount of time. However, if the same question was asked again, immediately after doing the mental arithmetic (37 + 15 + 12), then the correct response could be given without actually having to do the math again, by simply remembering the solution (“64”). But if, rather than asking the same question right away, you were asked the question after a period of time during which you had forgotten the answer, such a spaced repetition would require you to do the math again. The difficulty of doing the mental math again was desirable because it forced you to practice the skill (mental summation); simply remembering the answer did not. Spacing led to a desirable difficulty; massing was undesirably easy.

The role of feedback shares a similar relationship to the above concepts. The purpose of feedback is twofold: 1) to direct the learner to the correct knowledge or behavior, and 2) to assist the learner in understanding the correctness of one’s knowledge or behavior. One of the truisms of just about any training situation is that the instructor spends time with the learner only during the training session itself — the instructor will not be there when the learner must apply the trained skills. Thus, the goal of feedback is not to improve how to use feedback, but instead to learn from the feedback in order to learn how to self-evaluate and self-correct behavior later. Viewed in this way, the skill (self-reliance) is a process of becoming non-reliant on feedback. Training regimes in which feedback is provided without delay can cause the learner to become reliant on feedback to support the skill, creating what has been described as using feedback as a “crutch.”35 When the crutch is removed (i.e., when the instructor is no longer available) the informational support is lost and performance suffers.

Research with delayed feedback, and moreover, where self-evaluation is encouraged prior to feedback delivery, increases the difficulty of training compared to immediate feedback delivery. But the difficulty of training is desirable because it encourages the development of self-evaluation and self-correction skills. These skills provide the learner with the skills to adapt behavior “on the fly.” These are desirable skills because they are always with the learner and can be refined and improved with continued experience.

Few people would agree that extreme pressure situations are desirable. Yet, in many situations they are simply unavoidable, and this is especially true of law enforcement. What is desirable is how to best prepare the learner to perform learned skills when faced with these difficult situations. Training in the presence of high-pressure situations is clearly difficult and yet, if it can prepare the learner to perform under pressure when put on the spot, it could have life-saving consequences.

Implementing Desirably Difficult Training

There is no magic formula for how to implement desirably difficult training. Should some skilled behaviors be acquired under “easy” practice conditions before difficulty is introduced? Is there a benefit for blocked training at some point? If so, when should it be provided and then replaced with interleaving? Should instructors provide feedback often and immediately for a period of time before weaning the learner off the feedback? Should skills be developed before pressure situations are added? These are legitimate questions, the answers to which are necessarily dependent on the nature of the skills being learned and the context in which they are practiced. One could argue that a practice situation in which the learner is unsuccessful on 100 percent of the practice attempts would clearly be undesirable. And yet, a practice situation that leads to 100 percent success is equally undesirable. It is likely that “desirable difficulty” in real application requires arriving at an optimal balance of difficult and less-difficult practice conditions. The specific application of these ideas must be suitable to the nature of the skills to be trained, those instructors doing the training, and the trainees who are learning the skills.36 It should be noted that ideas like the ones posed in this paper have been promoted for applications such as sport coaching,37 medical training,38 education,39,40 and the training of Navy SEALs.41 There is good reason to believe that these ideas could be successfully applied to law enforcement training as well.

About Author

Tim Lee is a professor emeritus in the Department of Kinesiology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. He has published more than 140 research investigations in peer-reviewed psychology and kinesiology journals, is the author of Motor Control in Everyday Actions, and co-author of Motor Learning and Performance and Motor Control and Learning (both in their 6th editions). He served as an editor for the Journal of Motor Behavior and Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport and has been an editorial board member for Psychological Review. Tim has received a number of awards in honour of these scholarly efforts and continues to be involved in writing and research in “retirement”. He is an avid golfer who competes in local, national, and international tournaments.

- Schmidt, R.A., Lee, T.D., Winstein, C.J., Wulf, G., & Zelaznik, H.N. (2019). Motor control and learning: A behavioral emphasis (6th ed). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. [↩]

- Soderstrom, N.C., & Bjork, R.A. (2015). Learning versus performance: An integrative review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 176-199. [↩]

- Bjork, R.A. (1994). Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings. In J. Metcalfe & A. Shimamura (Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (pp. 185–205). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [↩]

- Bjork, R.A., & Bjork, E.L. (2020). Desirable difficulties in theory and practice. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9, 475-479. [↩]

- Lee, T.D., & Genovese, E.D. (1988). Distribution of practice in motor skill acquisition: Learning and performance effects reconsidered. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 59, 277–287. [↩]

- Dempster, F. N. (1988). The spacing effect: A case study in the failure to apply the results of psychological research. American Psychologist, 43, 627–634. [↩]

- Baddeley, A.D., & Longman, D.J.A. (1978). The influence of length and frequency of training session on the rate of learning to type. Ergonomics, 21, 627–635. [↩]

- Moulton, C-A. E., Dubrowski, A., MacRae, H., Graham, B., Grober, E., & Reznick, R. (2006). Teaching surgical skills: What kind of practice makes perfect? A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Surgery, 244, 400–409. [↩]

- Rohrer, D., & Taylor, K. (2006). The effects of overlearning and distributed practice on the retention of mathematics knowledge. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 1209–1224. [↩]

- Gates, A.I. (1917). Recitation as a factor in memorizing. Archives of Psychology, 6(40). [↩]

- Roediger, H.L., III, & Karpicke, J.D. (2006). Test enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17, 249–255. [↩]

- Rawson, K.A. & Dunlosky, J. (2012). When is practice testing most effective for improving the durability and efficiency of student learning? Educational Psychology Review, 24, 419–435. [↩]

- Green, M.L., Moeller, J.J., & Spak, J.M. (2018) Test-enhanced learning in health professions education: A systematic review. Medical Teacher, 40, 337-350. [↩]

- Rohrer, D., Taylor, K., & Sholar, B. (2010). Tests enhance the transfer of learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 36, 233-239. [↩]

- Pan, S. C., & Sana, F. (2021). Pretesting versus posttesting: Comparing the pedagogical benefits of errorful generation and retrieval practice. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 27, 237–257. [↩]

- Gerbier, E., & Topppino, T. C. (2015). The effect of distributed practice: Neuroscience, cognition, and education. Trends in Neuroscience & Education, 4, 49–59. [↩]

- Butler, A. C., Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. III. (2007). The effect of type and timing of feedback on learning from multiple-choice tests. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 13, 273–281. [↩]

- Swinnen, S.P., Schmidt, R.A., Nicholson, D.E., & Shapiro, D.C. (1990). Information feedback for skill acquisition: Instantaneous knowledge of results degrades learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 16, 706-716. [↩]

- Swinnen, S.P. (1990). Interpolated activities during the knowledge-of-results delay and post-knowledge-of-results interval: Effects on performance and learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 16, 692-705. [↩]

- Salmoni, A.W., Schmidt, R.A., & Walter, C.B. (1984). Knowledge of results and motor learning: A review and critical reappraisal. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 355–386. [↩]

- Schmidt, R. A., & Bjork, R. A. (1992). New conceptualizations of practice: Common principles in three paradigms suggest new concepts for training. Psychological Science, 3, 207-217. [↩]

- Rohrer, D., Dedrick, R.F., & Hartwig, M.K. (2020). The scarcity of interleaved practice in mathematics textbooks. Educational Psychology Review, 32, 873-883. [↩]

- Ste-Marie, D.M., Clark, S.E., Findlay, L.C., & Latimer, A.E. (2004). High levels of contextual interference enhance handwriting skill acquisition. Journal of Motor Behavior, 36, 115-126. [↩]

- Lee, T.D., & Carnahan, H. (2021). Motor learning: Reflections on the past 40 years of research. Kinesiology Review, 10, 274-282. [↩]

- Simon, D.A., & Bjork, R.A. (2001). Metacognition in motor learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 27, 907-912. [↩]

- Kornell, N., & Bjork, R. A. (2008). Learning concepts and categories: Is spacing the “enemy of induction?” Psychological Science, 19, 585-592. [↩]

- Hartwig, M.K., Rohrer, D., Dedrick, R.F. (2022). Scheduling math practice: Students’ underappreciation of spacing and interleaving. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. doi: 10.1037/xap0000391. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34990156. [↩]

- Low, W.R., Sandercock, G.R.H., Freeman, P., Winter, M.E., Butt, J., & Maynard, I. (2021). Pressure training for performance domains: A meta-analysis. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 10, 149–163. [↩]

- Oudejans, R.R.D. (2008) Reality-based practice under pressure improves handgun shooting performance of police officers. Ergonomics, 51, 261-273. [↩]

- Low, et al. [↩]

- Liu, Y., Mao, L., Zhao, Y, & Huang, Y. (2018). Impact of a simulated stress training program on the tactical shooting performance of SWAT trainees. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 89, 482-489. [↩]

- Oudejans [↩]

- Nieuwenhuys, A., & Oudejans, R.R.D. (2011). Training with anxiety: Short- and long-term effects on police officers’ shooting behavior under pressure. Cognitive Processing, 12, 277-288. [↩]

- Jacoby, L.L. (1978). On interpreting the effects of repetition: Solving a problem versus remembering a solution. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 17, 649-667. [↩]

- Schmidt [↩]

- Guadagnoli, M.A., & Lee, T.D. (2004). Challenge point: A framework for conceptualizing the effects of various practice conditions in motor learning. Journal of Motor Behavior, 36, 212-224. [↩]

- Hodges, N.J., & Lohse, K.R. (In press, 2022): An extended challenge-based framework for practice design in sports coaching. Journal of Sports Sciences, [↩]

- Guadagnoli, M.A., Poulin, M.-P., & Dubrowski, A. (2012). The application of the challenge point framework in medical education. Medical Education, 46, 447-453. [↩]

- Agarwal, P.L., & Bain, P.M. (2019). Powerful teaching: Unleash the science of learning. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass. [↩]

- Brown, P.C., Roediger, H.L., & McDaniel, M.A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. [↩]

- Roediger, H.L., Nestojko, J.F., & Smith, N.S. (2019). Strategies to improve learning and retention during training. In M.D. Matthews & D.M Schnyer (Eds.) Human performance optimization: The science and ethics of enhancing human capabilities (pp. 302-332). Oxford University Press. [↩]

This is a beautiful article with super important information, but so academic that most cops are not going to take the time to read it or digest it. If this could be paired it down to practical lessons learned and what every police academy needs to start implementing, and the kind of budget that would be required to have adequate training for the civilians to understand to vote for the right politicians and policies, then we will be talking business. Matt Tactical Chaplain

Thank you for this wonderful article regarding modern learning concepts. The unanswered question is what is the correct balance between information provided in a block manner and the testing and scenario training to reinforce it? We need to provide correct schema in scenario training under pressure but still need to provide related information in a didactic manner that may be spaced or blocked. When does spaced information become confusing with large amounts of information?

In other words, there can be a role for block training if supported by the other modalities you discussed in my opinion. Thank you.

Martin Greenberg MD

Excellent question, Martin. There is no clear answer provided by research. The most informed answer that I know is this: how much to combine blocked and spaced training depends on the experience level of the individual, the difficulty of the skill to be trained, and the complexity of the training conditions. When working with novices, difficult skills and/or complex training conditions then using blocked practice is advisable (at least initially). With more experienced individuals, easier skills and/or simpler training conditions then adding spaced or interleaved conditions of training is critical in order to challenge the learner with appropriate levels of desirable difficulty. Achieving a fine balance that will create an effective learning environment that produces skills that “stick” is the ultimate goal.

The article presents sound research, but as mentioned, it probably won’t be understood by many. In addition, how many academy training programs will or have implemented any of the methodologies referenced?

Check out the article on page 42 of the September issue of Chiefs Chronicle magazine. https://nysacop.memberclicks.net/assets/ChiefsChronicle/Chiefs%20Chronicle%20Magazine%20SEPT2022.pdf

The referenced curriculum is cutting edge using many of the concepts noted in the above article. Evaluation and refinement are ongoing. It is worth watching.